A call from that ‘certain someone’ pops up on your phone. What’s your response?

- Fear?

- Dread?

- Anger?

- Anxiety?

Do you tend to avoid the call by swiping it away and letting it go to voicemail? Hey, these things can be solved later over email, right?

Ahhh… the lure of the avoidance mindset: delay the discomfort under the falsehood that maybe… just maybe, the inevitable task will magically go away.

Experiencing uncomfortable physical and emotional sensations is actually perfectly normal. For example, going to a job interview shouldn’t exactly feel like a day at the spa (but wouldn’t that be nice).

So if job interviews, incoming calls from ‘that client’ etc. are so uncomfortable, how do we overcome these barriers of discomfort? (That is, without running away from them).

First, let me explain the science.

To help us take action, the body will produce various chemicals to keep us alert (epinephrine), focused (acetylcholine) and prompt us to move or speak (also acetylcholine).

To push through the frustration of novel challenges, the body produces dopamine (motivation and movement) to create a full body ‘yearning’ of sorts, pushing us to drive towards an outcome.

While this chemical cascade is generalised, our response choice is affected by past experiences.

Let’s look at the phone call example.

A phone call acts like a stimulus to your body’s nervous system. It alerts the brain through visual and auditory pathways (seeing the call on the screen and hearing the ring). These ‘signals’ prompt physical movement through chemical signals sent down the spinal cord through effector pathways (i.e. contracting muscles in the arm).

If this was the first time answering a call to ‘a certain someone’ – likely, it would be a reflexive movement. We’ve answered an incoming phone call so many times before, that our brain has well practiced neural pathways to minimise any need for mental effort.

However, past experiences, especially uncomfortable experiences, can change the way our brain ‘thinks’, thereby turning a reflexive movement into one that is made through careful deliberation.

In this phone call example, it pairs feelings of frustration, anger and anxiety (past experiences with ‘that certain someone’) with the incoming phone call (the stimulus).

The result?

(Most likely) avoidance… which is super unhelpful.

While avoiding answering the call (and likely distracting yourself with something pleasant, like scrolling a shoe sale) might seem like the best (or easiest) choice, you’re doing your brain a neurological disservice for the future.

Doing so effectively teaches your brain to ‘give up in the face of challenge’ by pairing the release of neurochemicals with the avoidance behaviours (shoe sale!) rather than leveraging their beneficial effects (alertness, focus and motivation) with pushing through the challenge of ‘that call’.

And yes, this is the same pathway that more sinister patterns are developed, such as drug and alchohol abuse, and food addiction.

So I ask again, with all of this (almost unconsciously driven) discomfort, how do we overcome it?

The tool: Master the breath

While we more often think about the brain controlling the body (top-down control), it’s important to capitalise on the benefits of the body’s influence on the brain (bottom-up control). Essentially, calming the body so your brain can think more clearly.

Indeed, various patterns of breathing will send different ‘signals’ towards your brain.

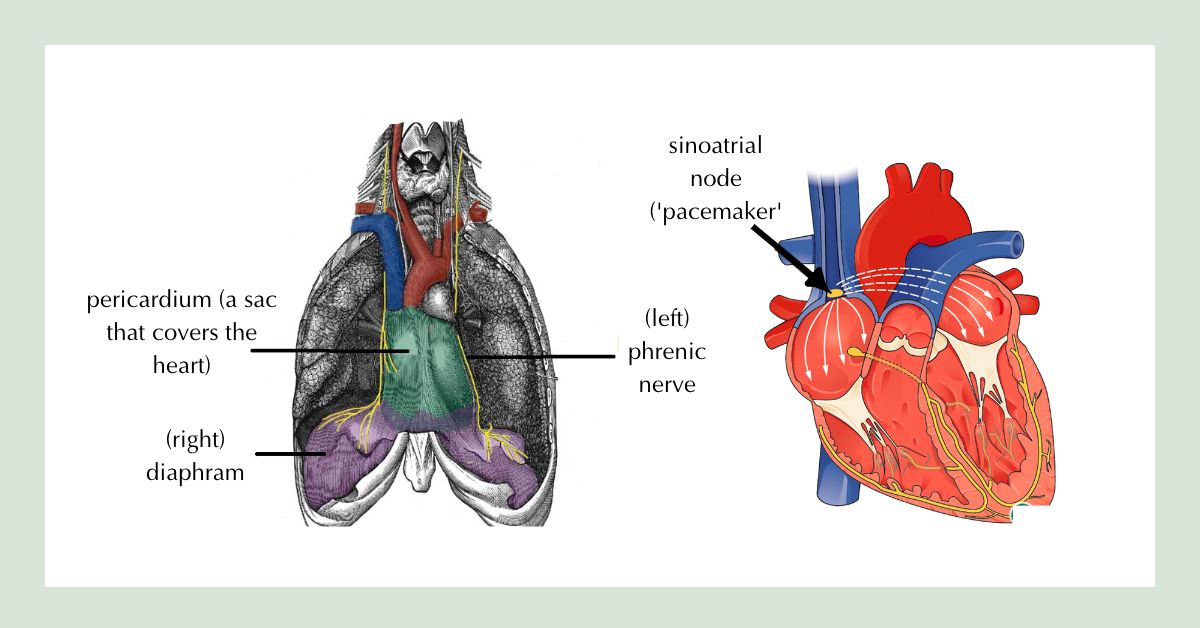

Brain-breathing connections include the phrenic nerve (connecting the nervous system from vertebrae C3-4-5 to the diaphragm) as well as electrical variations both towards and away from the sinoatrial node (the pacemaker of the heart).

Erratic, shallow and rapid breathing during stressful events can send ‘unsafe’ signals to your brain, inhibiting the ability to think strategically and effectively by removing the ability of the prefrontal cortex (PFC) to influence its logic on the situation.

(My chihuahua Eddie, as an example, does not have much of a prefrontal cortex, hence why it’s impossible to get him to ‘think’ logically in frightening situations. One time he ran 2km home, in the middle of the road, due to being frightened by a playful puppy).

Essentially, your brain receives information that says “why are you trying to solve a problem right now? You need to get out of here”.

That’s why the first step – simply ‘observing’ your breath – will automatically reduce erratic breathing, by forcing yourself to add a bit of logic to the situation and using your PFC to put on the ‘freak-out’ brakes.

The second step is to slow down your breathing. The easiest way to do this (in my view) is just focusing on the exhale. I kick things off with a ‘sigh’; a prolonged exhale while releasing any tension (especially in my shoulders and my palms).

A caveat: taking a simple breath will not fill your world with dancing unicorns and rainbows.