Is who you are shaped by the opinions and expectations of others? or are you really you? In this four-part article series, we’ll discuss how our life’s experiences affect who we think we are in contrast to who we really are. Each article will also include optional exercises for you to dig a bit deeper.

At-a-glance summary

- People can influence how we feel about ourselves through their reactions, which can create either positive or negative feedback loops.

- How we were parented, or treated by significant elders or caregivers, will also influence our perception of self.

- The result of these interactions can eventually determine our identity.

- How we respond, rather than react, is key to ensuring our identity stays within our control.

It’s disconcerting to know we start dying from the moment we are born, but it re-affirms an important message: the clock is ticking. All of us will die, yet only few of us will truly live. Then the question becomes, young grasshopper – how do we ‘truly’ live?

I believe it’s when we are proud of who we are, rather than who we ‘think’ we should be. Because how can you be happy living someone else’s life?

At least, that was my experience. Up until recently, I had this niggling feeling that I always had to ‘dial down’ who I really was. Like the real me was either ‘too unlikeable’ or ‘too much’ to fit in. Hence why I’d like to spend the next four weeks diving into the question: what factors shape who we are? Of course, there are many. But in this multi-part series we’ll tackle four influences based loosely on a model by Michael Argyle (1).

- The reactions of others. How does the reaction of others affect us? For example, does the number of social media followers or likes we receive on a post affect the way we feel about ourselves?

- Comparison with others. When we’re scrolling through Instagram, do we assess ourselves based on how we rank compared with others?

- Social roles. How does our place in society affect the way we feel about ourselves? Does your profession or your role make you feel good about yourself? Or does it make you feel down?

- Identification with others. If we believe that we learn from observing others, how do you think the people around you influence you and your behaviour? In a positive way? Or negatively?

Whether these experiences are positive or negative, they leave an indelible imprint on our psyche, shaping the person we are, and also who we will become.

In this post, we’ll start with number 1 – how other people influence who we are. As you read and learn, I’d invite you to put yourself into the concepts. What do they make you think about? And why?

The Reaction of Others

Back in my dating days, I was a monkey swinging from relationship to relationship, only feeling like a person of worth IF someone liked me. In one instance, I was more determined than ever to impress a guy. My strategy was to read out a passage from a book that would be classified as a ‘smart person book’ (side note: I couldn’t understand a damn thing).

Nevertheless – I read out loud thinking it would make him like me more. The word ‘chasm’ came up. I had never come across the word so I pronounced it with a soft c, so it sounded like tschasem rather than its proper pronunciation of kazem. What did he do? Rather than gently correcting me, he laughed and made fun of me. So what did I do? I protected my hurt ego by making up a story.

‘Well that’s how we say it in Canada’.

(To this day I have no idea what I was thinking and how that would pass as even remotely legitimate.).

Why did I defend myself this way? Because being wrong can make us feel ashamed, stupid and dumb. By deflecting the feeling of blame from me to him, I was protecting myself from further hurt.

The take-home message? Regardless of how confident you are, we all care about people’s reactions. And this is far from new…

Ugly Duckling and the Swan

In a 1938 book, the behavioural psychologist Dr Edwin Ray Guthrie (2) shared the results of an experiment which remains relevant today. Male students were asked to give attention to a shy female classmate, interested to find out if it made her feel more attractive and desirable. At first, the woman thought they were playing a prank on her; however, slowly but surely she started to change her behaviour, eventually enjoying the attention, and even changing the way she dressed and did her hair.

Most surprisingly, the change in her personality was not just with these male students. Men who were completely unaware of the experiment also treated her like an attractive and desirable woman. The more attention she received, the more effort she would put into her appearance. The more effort, the better she looked and the more attention she got. It was a continuous and positive feedback loop.

But here’s the clincher: the original men from the study eventually ‘forgot’ they were in an experiment and began competing for the attention of the “ugly duckling who had turned into a swan”. It was a sort of self-fulfilling prophecy.

Pygmalion in the Classroom

Another great example of the self-fulfilling prophecy is a famous 1968 study (3) called ‘Pygmalion in the classroom’. The goal was to determine if the behaviour of teachers affected the academic ability of students. For this study, researchers told teachers certain students demonstrated ‘unusual potential for intellectual growth’ from their results on a specialised IQ test. In reality, the IQ test was made up, and the students were chosen at random.

Although the teachers’ beliefs about their students were falsely fabricated, their high expectations likely created an unconscious change in their levels of attention to these students, serving once again as a self-fulfilling prophecy. Put simply, because the teachers expected that specific children would eventually show greater intellectual development, those children did indeed show greater intellectual development.

“When we expect certain behaviours from others, we are likely to act in ways that make the expected behaviour more likely to occur”(3)

How does this happen?

If we’re treated in a kind, attentive way we feel good about ourselves and will likely repeat the behaviours that lead us to receiving those niceties. But what if we’re treated poorly, such as being told we’re clumsy, stupid or fat? Will we interpret those impressions as truth? Under certain circumstances such as when we have low self-esteem, absolutely. The irony is, we didn’t initially think these things of ourselves. But eventually we’ll use these terms to describe ourselves, regardless of whether they are true or not.

Unconscious (and conscious) judgement

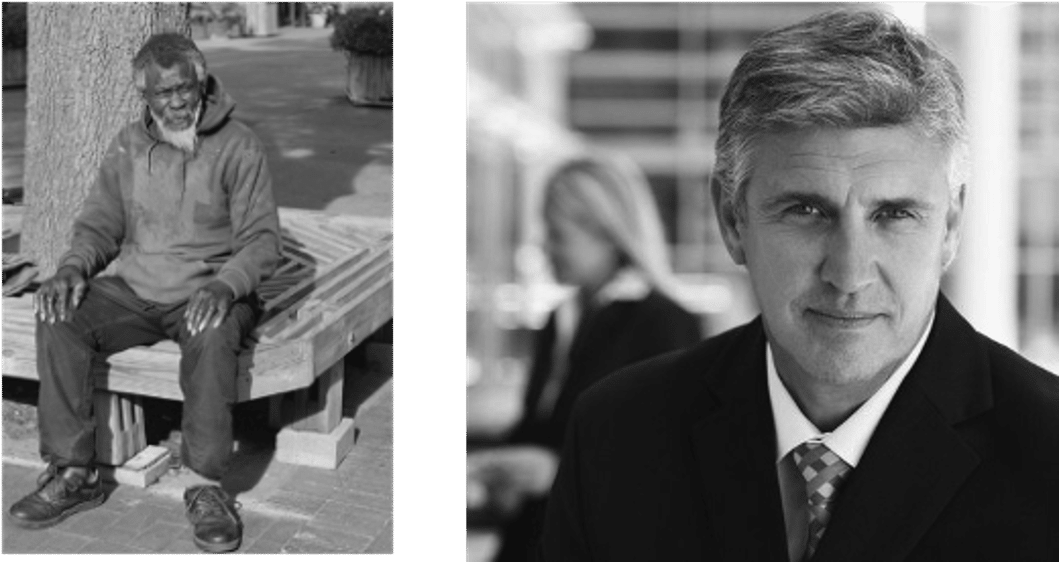

Here’s an example. Have a look at these two photos, what is your first impression? (Remember that you are not telling anyone your answers, so I invite you to be honest).

What is the typical narrative around persons of lower socioeconomic status, for example, the man in the photo? Do we think of them as less educated? drug users? criminals?

What is the typical narrative of people in business, for example, the clean-shaven man in the photo? Are they educated, hardworking and good citizens?

The fact is, whether they are spoken to the person out loud or not, the words we choose to describe a person aren’t just random words, they have the power to determine what we think of a person, and therefore how we treat that person. This is called labelling bias, which happens when we label people a certain way, and this then makes us treat them in biased ways (4)

I’d invite you to take some time to think about whether:

1. Someone’s attention ever made you feel better about yourself. Why do you think the attention felt good from them in particular? Would it be the same if it came from someone else? Why or why not?

2. Reflect on how the reaction of another person might have influenced how you describe yourself. For example, did someone ever say something to describe you that made you subsequently conscious of yourself?

Parental Influence

If we incorporate the opinions, attitudes and reactions of others and absorb them into our own concept of self, our parents and caretakers will as well. A study by Stanley Coopersmith in 1967 (5) investigated this hypothesis, specifically, that a child will value themselves only as much as their parents value them.

In this study, he observed hundreds of boys while they grew up. The boys were categorised as being either low, neutral or high in self-esteem. Those that were low in self-esteem were reported as sad, fearful, isolated, self-conscious, underachievers and sensitive to criticism. In contrast, boys high in self-esteem were confident, resilient, academically successful and popular.

In this study, they found that the parents of the low self-esteem boys treated their children ‘inconsistently’ – meaning that the child didn’t know what reaction they were going to get out of their parents. For example: Imagine you spill some milk. One time your parents lose the plot, and the next time they barely say a word. The authors hypothesised that the inconsistent treatment and unpredictable reactivity lead the child into questioning his own behaviour.

The researchers also found that parents of the low-self-esteem group did not ‘check-in’ with their children as often, nor did they provide them with regular affection. For example: Imagine you’re bullied at school and you return home feeling visibly sad and deflated. Rather than check up on you and give you a hug, your parents just tell you to start your homework and ignore your overt feelings. In this case, would you be more or less likely to believe that you deserved the treatment of the bullies? Indeed, what is reinforced becomes easier to believe.

In contrast, parents of the high-esteem group displayed more warmth and affection but also asserted their authority, had clearly defined limits, while showing them respect by allowing their children to talk openly about their concerns and feelings.

Can you relate to any of these findings? Can you see how your parents may have influenced how you feel about yourself?

And please for the love of God, this isn’t to point fingers and blame anyone, it’s to try and put pieces of the puzzle together so you can understand your story more clearly.

What can we do?

These are only a few of the notable historical studies that show how the reactions of others can unconsciously influence and uniquely shape who we are. And while of course we don’t need to do much about positive influences, the question is – how can we manage those that may impact us in unhealthy ways? The most effective way is to respond rather than react to other people’s reactions.

What I mean by this is the world will never be one of rainbows and farting unicorns. Even if you’re Mother Teresa or Gandhi, you’re going to be up against situations where other people can potentially influence you in unhelpful ways.

So the trick isn’t to stop this from happening, but giving yourself some time and space to respond, rather than react. Kind of like having a moment to step into your own personal cone of silence, allowing you to slow things down and really think about things in a less emotive way.

Reactions vs Responses

What’s the difference between reactions and responses? They are two distinct terms that refer to different ways of processing information which results in two different outcomes. A reaction is an automatic and instinctive behaviour that occurs without much conscious thought or effort. On the other hand, a response is a more deliberate and conscious behaviour that is intentional and purposeful. The critical importance of understanding the difference is that it helps us better understand our own behaviour and in particular that of others.

Knowing whether we are reacting impulsively or responding intentionally can help us make better decisions, communicate more effectively, and manage our emotions more skilfully. For example, a reaction would be becoming angry and aggressive to someone cutting you off in traffic.

A response would be feeling that anger and even having the urge to be aggressive, but first taking a deep breath so you can consciously, rather than unconsciously, choose to respond. Understanding the difference between the two can help you avoid getting caught up in unhelpful patterns of behaviour and improve your relationships with others.

There is also evidence that responding rather than reacting may positively impact physical health. One study found that individuals who responded to stressors in a more adaptive and deliberate manner had lower levels of the stress hormone cortisol and better cardiovascular health than those who reacted impulsively (6). Two studies showed mindfulness-based interventions, which teach individuals to respond rather than react to stressful situations, can lead to improvements in a range of physical health outcomes, such as lower blood pressure and improved immune function (7,8).

This is important as chronic stress (strongly linked to reactive behaviour) is associated with cardiovascular disease, weakened immune function, and increased risk of depression and anxiety (9) as well as increasing susceptibility to infection and impaired wound healing (10).

Emotional Agility Download

| REACTION | RESPONSE |

| Quick, instant | Slow, measured |

| Emotional | Thoughtful |

| Aggressive | Assertive |

| Increases conflict | Decreases conflict |

| Promotes more reactions | Promotes resolution |

Quick tip:

Many of us work at computers, right? How many times have you received a curt email and your first thought is to become the ultimate keyboard warrior and send a nasty email right back? We’ve all done it so don’t be ashamed. Here’s what you could do: simply write REACT or RESPOND on a Post-it Note and put it somewhere in your view. Every time a nasty email pops up, take a breath and weigh up the pros and cons of how you choose to respond.

Final words

Our sense of self is influenced by various factors, with the reactions of others being a significant one. We all care about how others perceive us, that’s normal and, one could argue, even healthy. But we need to be aware of times when the reactions of others can shape our behaviour, personality, and even our future in unhealthy ways. Positive feedback and attention can lead to a self-fulfilling prophecy of success and growth, while negative reactions can lead to shame and self-doubt. Understanding the power of other people’s reactions can help us become more self-aware and live a life that is true to ourselves rather than trying to please others.

We simply cannot control how others react to us, but we can control how we react to them and how we choose to shape our own sense of self.

Dr K x

P.S. if this article resonated I’d encourage you to read my last blog “Here’s when you should care about what other people think of you” – I think you’d benefit.

‘Between the stimulus and the response there is a space, and in this space lies our power and freedom.’

References

- Argyle M. Social encounters: Contributions to social interaction. 1st ed. Piscataway, NJ: Aldine Transaction; 2008.

- Guthrie ER. The psychology of human conflict: The clash of motives within the individual. New York: Harper Brothers; 1938.

- Rosenthal R, Babad EY. Pygmalion in the gymnasium. Educ Leadersh 1985;43(1):36-39.

- Fox JD, Stinnett TA. The effects of labelling bias on prognostic outlook for children as a function of diagnostic label and profession. Psychology In The Schools 1996;33(2):143-152. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6807(199604)33:2%3C143::AID-PITS7%3E3.0.CO;2-S

- Coopersmith S. The antecedents of self-esteem. San Francisco: W.H. Free- man; 1967.

- Sliwinski, M. J., Almeida, D. M., Smyth, J. M., & Stawski, R. S. (2015). Intraindividual change and variability in daily stress processes: Findings from two measurement-burst diary studies. Psychology and aging, 30(3), 583-598.

- Buric, I., Farias, M., Jong, J., Mee, C., & Brazil, I. A. (2017). What is the molecular signature of mind-body interventions? A systematic review of gene expression changes induced by meditation and related practices. Frontiers in immunology, 8, 670.

- Creswell JD, Taren AA, Lindsay EK, Greco CM, Gianaros PJ, Fairgrieve A, Marsland AL, Brown KW, Way BM, Rosen RK, Ferris JL. Alterations in Resting-State Functional Connectivity Link Mindfulness Meditation With Reduced Interleukin-6: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Biol Psychiatry. 2016 Jul 1;80(1):53-61. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.01.008. Epub 2016 Jan 29. PMID: 27021514.

- McEwen, B. S., & Gianaros, P. J. (2010). Central role of the brain in stress and adaptation: Links to socioeconomic status, health, and disease. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1186(1), 190-222.

- Glaser, R., & Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K. (2005). Stress-induced immune dysfunction: implications for health. Nature Reviews Immunology, 5(3), 243-251.

- Prisoners of Our Thoughts: Viktor Frankl’s Principles for Discovering Meaning in Life and Work. Second Edition by Alex Pattakos, Ph.D. Published by Berrett-Koehler Publishers. 2010.